“No one can appreciate science if he does not live in it.”

— Michael Polanyi, Science, Faith, and Society

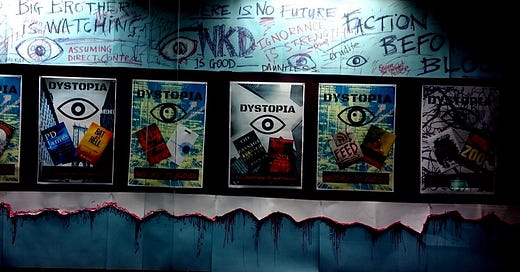

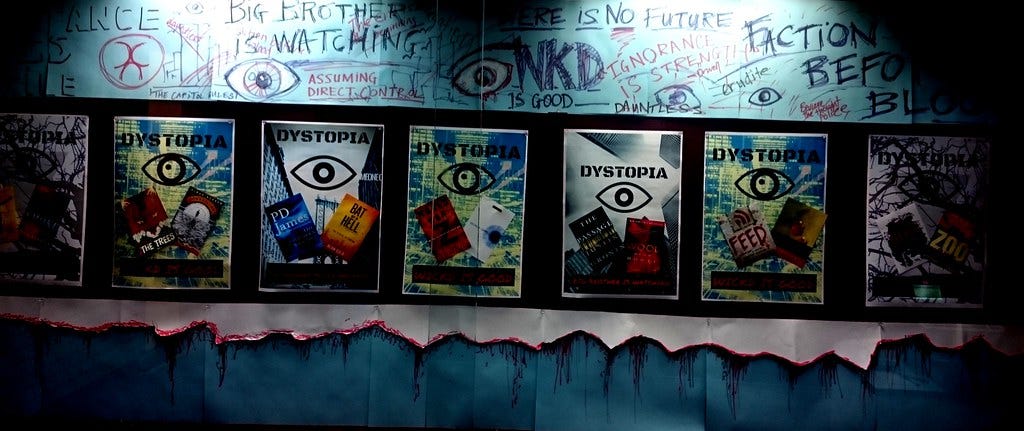

Imagine a world where scientific progress is dictated not by curiosity but by central authority. Where research is judged not on its merit, but on whether it aligns with prevailing political or ideological trends. Where objectivity is seen as a myth, and science is reduced to a tool for achieving preordained goals.

Now, ask yourself: Are we already there?

Michael Polanyi’s Science, Faith, and Society (1946) may not be the first book people reach for when debating the role of science in modern society, but maybe it should be. In this slim yet profound work, Polanyi—a physical chemist turned philosopher, and one of the last great polymaths—challenges the dominant view of science as a purely objective, algorithmic process. He argues that scientific discovery is, at its core, an act of faith. Not blind faith, but faith in a deeper reality that scientists believe is out there, waiting to be understood.

If this sounds radical, it’s because it is. And yet, Polanyi’s insights may be exactly what we need to reclaim science from both ideological capture and the technocratic mindset that treats it as a mere tool for control rather than an open-ended pursuit of truth.

The Myth of Pure Objectivity

The standard view of science—taught in schools, promoted in the media, and embraced by policymakers—goes something like this:

Science is an impersonal, neutral method.

Scientists follow strict procedures to uncover objective truths.

The system is self-correcting, driven purely by empirical evidence.

But Polanyi calls this a dangerous oversimplification. He argues that science is not just a mechanical process of accumulating facts; it is a deeply human activity, requiring personal judgment, intuition, and a shared sense of purpose among scientists.

Consider how major breakthroughs actually happen. Do scientists arrive at new theories by coldly crunching data, like a computer? Or do they rely on something deeper—insight, creativity, and a sense of what “feels right” before it’s even proven?

Polanyi argues that true discovery is always guided by an unprovable but necessary belief that the universe is intelligible. A scientist does not simply follow rules; they operate within a tradition of inquiry, learning from those before them, absorbing the tacit knowledge of what makes good science, and trusting that truth is worth seeking—even when no immediate rewards exist.

In other words, science is a community of faith.

The Invisible Hand

One of Polanyi’s most compelling arguments is that science, much like a free market, works best when it is self-regulated.

Just as an economy thrives when individuals pursue innovation without government micromanagement, science flourishes when researchers are free to explore—without the constraints of ideology, central planning, or bureaucratic oversight dictating what they should find.

This is where he launches a blistering critique of totalitarian science—the kind seen in Soviet Russia under Trofim Lysenko, where politically approved ideas replaced genuine inquiry. Lysenko rejected genetics in favor of Marxist-friendly pseudoscience, and as a result, Soviet agriculture suffered catastrophic failures.1 Polanyi warns that whenever external forces (whether political, corporate, or cultural) attempt to dictate the direction of science, they destroy the very conditions that allow knowledge to grow.

Yet, Polanyi’s warning isn’t just about totalitarian regimes. Even in democratic societies, science is at risk when institutions prioritize conformity over curiosity, consensus over questioning. When grant funding, peer review, and institutional prestige are shaped by what is politically acceptable rather than what is scientifically rigorous, we may not be burning heretics at the stake—but we are, in a sense, silencing them.

Necessary Faith

At this point, you might be wondering: Is Polanyi really suggesting that science and religion are the same thing?

Not quite. He recognizes the difference between religious faith and scientific faith. Religious faith is about commitment to the unseen; scientific faith is about commitment to an unseen order—a belief that reality is structured in a way that we can eventually grasp.

This is what drives scientists to keep searching, even when evidence is incomplete. It’s why Einstein could confidently assert that…

“God does not play dice with the universe”

… long before quantum mechanics began to be comprehensible. It’s why Copernicus pursued heliocentrism despite lacking proof at the time. It’s why researchers today spend decades searching for dark matter, evidence to support string theory, and the origins of consciousness.

Science is not the opposite of faith—it depends on it.

Why This Matters

Half a century later, Polanyi’s arguments feel more urgent than ever. We live in a time where:

Science is increasingly entangled with politics and corporate interests.

Scientists are pressured to align with ideological narratives or risk professional exile.

Public trust in science is eroding, precisely because it is often wielded as an authoritarian hammer rather than an open-ended quest for truth.

What would Polanyi say about our current predicament? Probably, that the health of science depends on intellectual freedom. It must remain a living tradition, where individuals pursue truth for its own sake—not for power, profit, or prestige.

“The quickest impression on the scientific world may be made not by publishing the whole truth and nothing but the truth, but rather by serving an interesting and plausible story composed of parts of the truth with a little straight invention admixed to it. Such a composition is judiciously guarded by interspersed ambiguities, will be extremely difficult to controvert, and in a field in which experiments are laborious or intrinsically difficult to reproduce may stand for years unchallenged. A considerable reputation can be built and a very comfortable university post be gained before this kind of swindle transpires — if it ever does. If each scientist set to work every morning with the intention of doing the best bit of safe charlatanry, which would just help him into a good post, there would soon exist no effective standards by which such deception could be detected. A community of scientists in which each would act only with an eye to please scientific opinion would find no scientific opinion to please. Only if scientists remain loyal to scientific ideals rather than try to achieve success with their fellow scientists can they form a community, which will uphold these ideals.”

If we reduce science to a tool for controlling society, we risk killing the very thing that makes it powerful. But if we recognize, as Polanyi did, that science thrives only when it is allowed to evolve organically—guided by tradition, personal knowledge, and a shared faith in reality—then perhaps we can restore what has been lost.

The Future of Science and Faith

Polanyi’s vision of science is one of humility and openness. He reminds us that no scientific system, however advanced, will ever fully encapsulate reality. There will always be more to discover, more to question, and more to challenge.

That’s not a weakness—it’s science’s greatest strength.

So the next time someone tells you that “the science is settled,” or that scientists must align with a particular ideology, remember Michael Polanyi’s warning: Science is not a machine. It is a living tradition, passed down through faith, curiosity, and an unyielding belief that truth is worth seeking.

The moment we forget that is the moment we stop doing science at all.

Lysenko denied the existence of genes and Mendelian genetics, instead promoting a "Marxist genetics" that claimed unlimited transformation of living organisms through environmental changes. He rejected natural selection and proposed theories such as the inheritance of acquired characteristics, which aligned with the Soviet ideology of creating a "New Soviet Man". As a result of Lysenko's influence and Stalin's support, his methods were widely implemented in Soviet agriculture. These included planting seeds very close together and forbidding the use of fertilizers and pesticides. The consequences were catastrophic:

Widespread crop failures and rotting of wheat, rye, potatoes, and beets.

Millions of people died of starvation, with estimates ranging from 30 to 45 million deaths.

Soviet agriculture suffered significant setbacks, and crop yields drastically decreased.

The implementation of Lysenkoism not only led to agricultural disasters but also severely hindered the progress of Soviet biology and genetics research for decades

Reznik, S., & Fet, V. (2019). The destructive role of Trofim Lysenko in Russian Science. European journal of human genetics : EJHG, 27(9), 1324–1325. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41431-019-0422-5